Tool 12

Why: Our ideas of global competences and how they can be identified in practice in connection with recruitment and development activities are often out-of-date or rest on assumptions that may have no basis in reality. This dialogue tool can be used as a source of inspiration for an inspection of the assumptions that drive our identification of ”the good global leader/employee” or as a basis for a debate on skills in an organization facing (further) internationalization or globalization.

What: Nine myths about global competence may be revealed by two global competence models. There are questions for reflection on each of the nine myths, to challenge the gut feel and ”common sense” of managers and HR professionals and encourage them to consider whether their view of global leadership is coloured by fact or fiction. The nine myths are then summarized in a ”global mindset reality check”, where you can assess your own or your organization’s view of global mindset competence.

How and who: The tool can be used by managers and HR professionals, individually or in groups, to get better at identifying and developing their own and other people’s global competence, including casting a critical eye over their existing and future practice.

This tool uncovers nine myths about global leadership, as discussed by the members of the Academy and revealed in the literature and from research projects and invited guests from Denmark and abroad:

Each myth is expanded on below, together with some questions for reflection which invite you to check and discuss what is fact and what is fiction in your own global practice and organization. At the end, you can take a test to assess your own and your colleagues’ perception of global mindset competence.

It is easy to fall into the idea that you simply can’t have enough global mindset, and that everyone should have it. And it is undeniably difficult to find anyone against global mindset: it sounds up-to-date, fine and right – and who would want to be accused of a local, domestic or ethnocentric mindset? There is a social pressure to be ”on trend”, and so it sounds sensible to say that, if only all of the staff were more globally minded, everything would be much easier. And there is no doubt that both world peace and international companies suffer from a lack of global vision. But global mindset as a kind of unisex one-size-fits-all solution may simply be out of step with the company’s strategic reality. In any case, it will often be unrealistic to develop global mindset in everyone in the short or the medium term – do we have the cognitive bandwidth to develop it in everyone? And even if we do, would it be such effective use of resources if many people’s jobs have only a limited global element in them?

In what way is global mindset necessary to realizing current or future strategic objectives – for yourself as a leader or for your team/department?

Why should the company’s employees have a global mindset? How does it help you in a practical sense?

What specific behaviour do you see as the result of the desired global outlook in yourself and others? How would the way you carry out your tasks be different if you had more global mindset?

Pankaj Ghemawat, Professor of Global Strategy and author of the book ”World 3.0: Global Prosperity and How to Achieve It” (2011) believes that many of us are exponents of ”globaloney”, resulting in greatly exaggerated ideas of the extent and consequences of globalization. Part of Ghemawat’s explanation for this failure to recognize the more moderate scope of globalization (according to him) is that decision-makers in global organizations typically live more globalized (working) lives than the rest of the population, including their own employees. They overstate the extent of globalization and its implications for their staff and the company as a whole. As we know, above the clouds it’s always sunny, and with a bird’s-eye (or top management) view, the world may look more flat, as a bestselling book on globalization put it. For the vast majority of employees and managers in the global world, working life is quite earthbound and visibility more limited, and the Earth is still round.

Do top management or other layers of management have a realistic idea of the company’s need for global mindset – or do they confuse their own competence needs with other people’s? How can you as a leader make top management understand how the global aspect affects your part of the organization?

Should all groups of employees display a global mindset in the same way? And how can you as a leader define how global mindset in your function might be understood differently than in the upper layers of management?

How do you ensure that the global mindset of top management is also developed and challenged?

A practical and easy shortcut to identifying global competences is to look at whether an employee has global experience. That certainly sounds very good, but it is not necessarily so. The connection between previous experience from e.g. postings abroad and existence of global competence is more complicated than that, as much depends on whether earlier expat experience or global working was positive. Global experience can also inhibit the development of global competence, as illustrated by the model below:

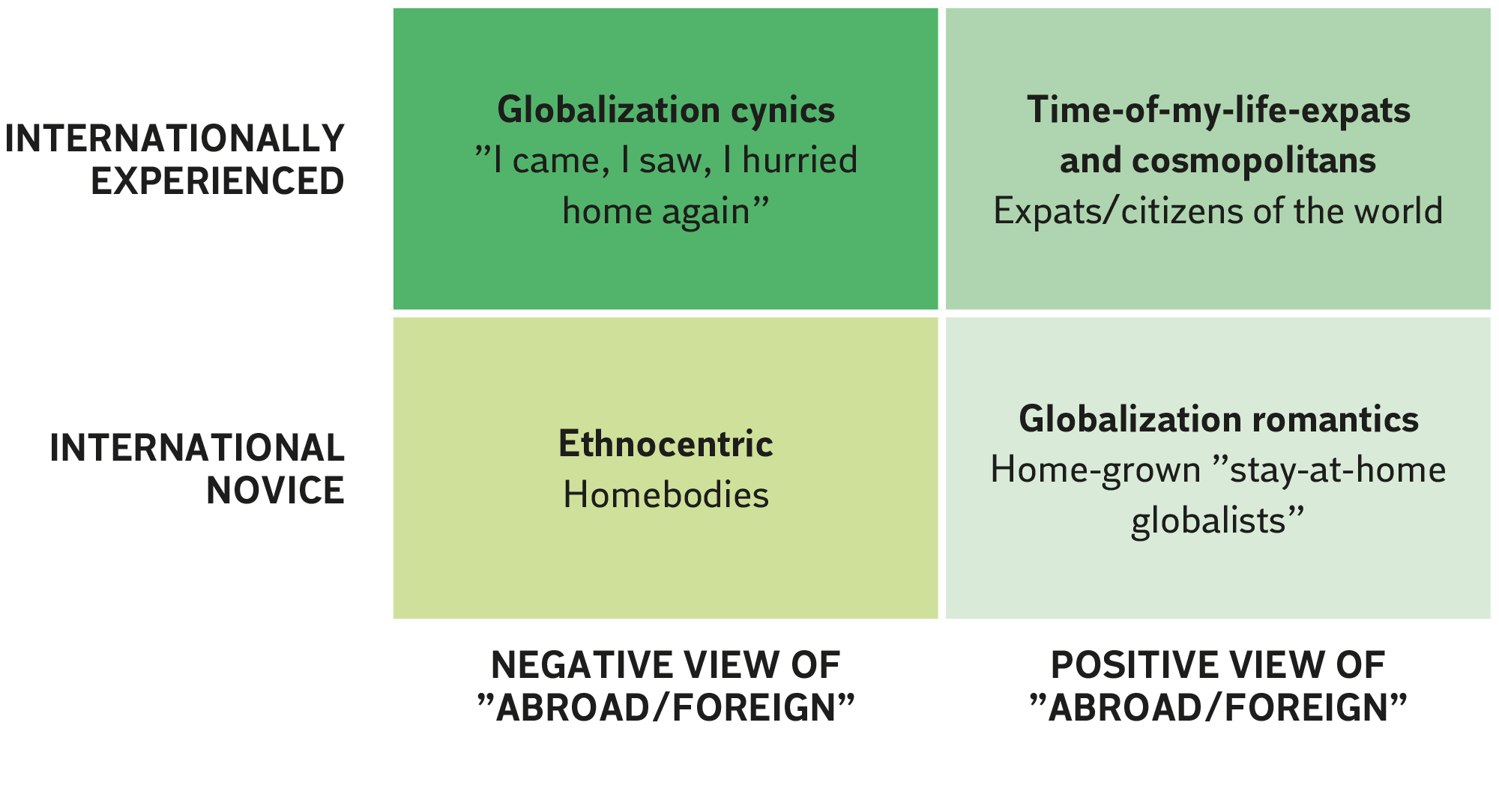

Figure 12.1: International experience and view of ”abroad”. From Nielsen (2014)

In the top half of the diagram we have two groups of people who have international experience. In the top right corner we have people with expat backgrounds, whose experiences have given them a very positive view of ”abroad” – we call them the ”Time-of-my-life-expats” expatriate managers/globetrotters, and they are typically the ones we look to recruit/promote when we regard experience abroad as a positive factor on the CV. In the top left corner of the figure is a group of people who have had experience abroad, but it has been negative. It is this group of globalization cynics, who perhaps ”came, saw, and hurried home again” that we need to be extra careful of, because there is a risk that they will not actually be able to turn the global experiences they have had into something that can be used constructively in the future. Perhaps the opposite.

In the bottom half of the diagram we have two groups of people without any international experience, one with a positive view and one with a negative perception of ”abroad”. For these two groups, the same principle of not taking anything at face value applies. The group of ”ethnocentric homebodies” perhaps covers people who do not feel properly suited to new tasks, but the group of otherwise positive globalization romantics may simply be ill-equipped to tackle the complications and challenges to their identity that follow in the wake of international collaboration.

What bearing does international experience have on your assessment of global competence? For example, what emphasis do you place on international experience in recruitment activities, staff appraisals and talent development?

Are some employees excluded from active involvement in global collaboration because of a lack of skills? What can you as a leader do to ensure that more people in your team or department feel ready to engage in global collaboration?

What type of development support is needed to ensure that global enthusiasm is preserved and developed in contact with ”otherness”? How can you as a leader facilitate this development process?

A lot of resources are spent developing leadership competence, and the market for the development of global skills is bursting with intercultural skills development, global sensitivity training and global leadership programmes. And the leaders are undeniably a key group. Two major authorities on global mindset, Gupta and Govindarajan, note however that: Although we contend that returns to investment in cultivating a global mindset would always be positive, we do not expect them to be uniform. The value added by global mindset, and the value subtracted by its absence, is likely to be strongest in the case of those individuals who are directly responsible for managing cross-border activities, followed by those who must interact frequently with colleagues from other countries” (Gupta & Govindarajan, 2001, p. 124). It is striking here that the word ”leader” is conspicuous by its absence. This turns the focus on an aspect which has often come up in discussions at the Global Leadership Academy – the fact that an ever-growing number of employees come into contact with, and therefore need, global collaboration skills. But where are they in the companies’ efforts to develop global competence? In the Academy we have met with great interest, but found no concrete initiatives specifically directed at ”global mindset for employees”. We may then ask, if leadership is something that managers and their staff work together to bring about, what type of ”global mindset followership” competence should then match the manager’s ”global mindset leadership” competence?

What are your selection principles for deciding which employees should take part in global development programmes or activities? Are your needs as a leader addressed in the existing programmes – and if not, what alternative development paths exist?

Are there new/other groups of employees whose work duties – whatever their geographical location or place in the hierarchy – are global and so should be included? Are there employees who you overlook when prioritizing resources for global development activities?

If there is global mindset leadership, how is global mindset followership practised in your organization? Do your employees know how best to act ”globally” in their job role?

Managers dominate the competence development landscape – not just compared to ordinary employees but also compared to types of leadership that do not involve direct staff responsibility. To begin with, there was a more or less unspoken assumption in GLA circles about the work on global leadership that it was most relevant to concern ourselves with global leaders with staff responsibility. However, this assumption was strongly challenged as our work progressed. Complex organization structures, matrix models and other forms of horizontal collaboration are becoming more and more widespread and raise the question whether global leadership and mindset should necessarily be reserved to the part of leadership work that is hierarchically structured. At the same time, a study of global leaders’ views of the challenges they faced in global working showed that it was precisely the parts of the job that had to do with collaboration with people over whom the leader had no staff responsibility which were felt to be more challenging (Nielsen and Nielsen, 2016). In matrices and multi-stranded collaboration structures, the traditional management skillset was even more stretched than in a globalized version of classical, home-based leadership.

What is your experience of challenges relating to global leadership when it comes to tasks that involve or exclude staff management?

How are leadership functions that do not involve direct staff responsibility covered in your global competence development?

Is there a need for a targeted effort in relation to horizontal, boundary-crossing matrix management – including for leaders who are already well-versed in situations where they have had direct staff management responsibility?

As with most other investments, we pass a point somewhere along the way where any further input gives diminishing returns – the curve does not simply continue steadily upwards to infinity. Although many Danish companies may think there is some way to go before the curve flattens off, a discussion of how much global mindset they actually need could be appropriate. In this connection, we might also discuss whether more global mindset is always desirable – whether in fact we can simply have too much global mindset? There is reason to believe that you can in fact have too much of a good thing when it comes to developing global mindset. One global leader reflects on this question: ”Being too global is when you embrace China, India and Russia so much that you forget to listen to South Jutland. If you become too global, you lose the national perspective, which is also important.” Once you become hyper-globally minded, you may also lose the ability to deal with other people who have a more local outlook – thereby losing the ability to work together with a large part of the Earth’s population, and missing the whole point of developing global mindset. This issue was addressed by one of the research reports produced as part of the Global Leadership Academy’s knowledge development activities, which looked more closely at an international group of extremely mobile and globally experienced employees (Storgaard and Skovgaard-Smith, 2012). In this report, some of the globalists interviewed state, for example, that: ”Once home has become potentially anywhere, you can’t go back as it’s expressed.” (Storgaard & Skovgaard-Smith, 2012, p. 56), and ”I do identity myself as more of a global person rather than Australian. Because I don’t identify with the Australian sort of insular mindset anymore” (Storgaard & Skovgaard-Smith, 2012, p. 56). A crucial point is then the extent to which acquiring a global mindset supplants national/local ties, and whether this ”cutting loose” results in a negative view of one’s own country and other ”local” thinking. This is illustrated by the figure below:

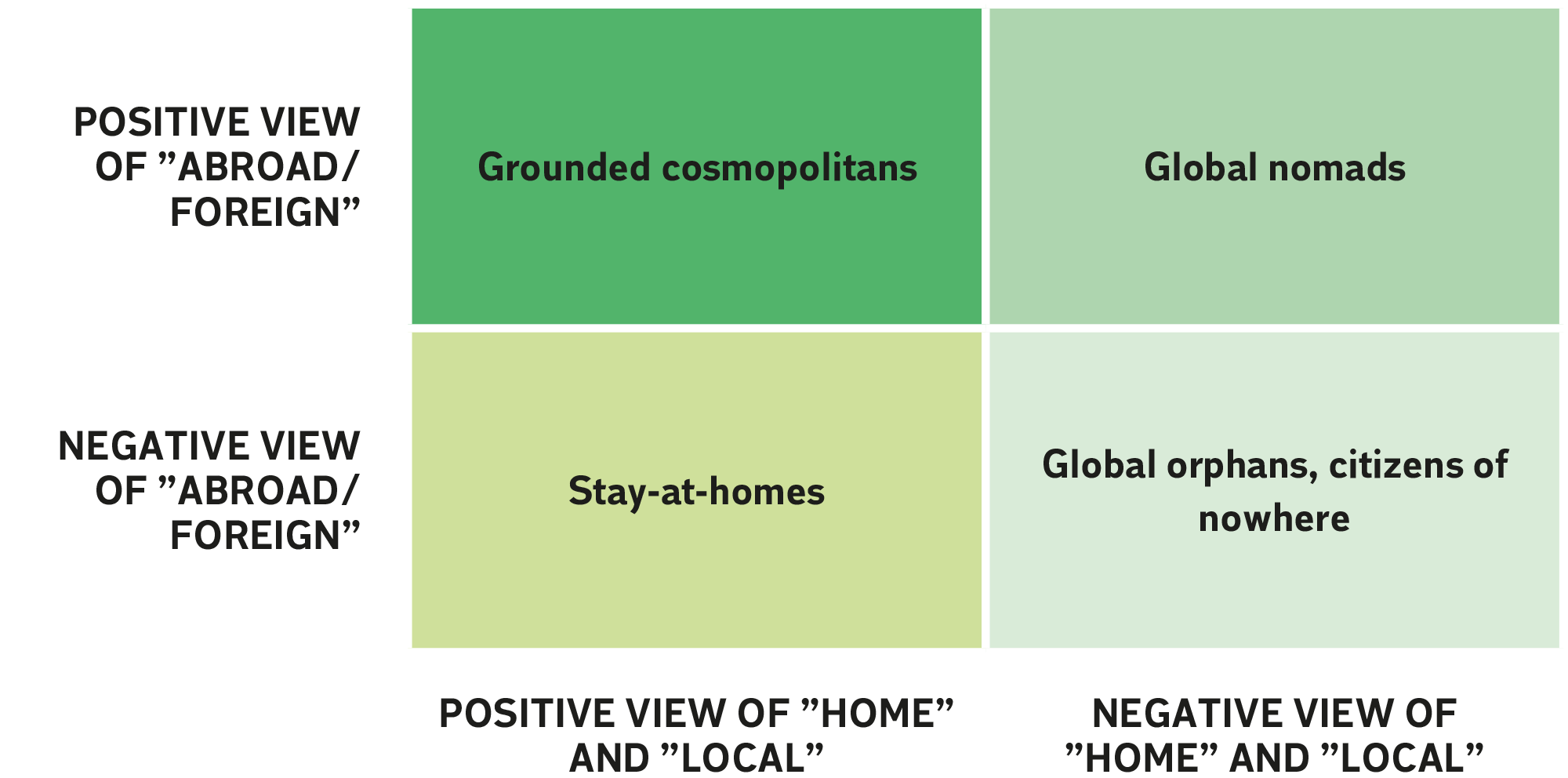

Figure 12.2: Home and away – positive and negative. From Nielsen (2014)

This combines two axes: The perception of ”abroad”, and the perception of ”home” and the local background. In the top right corner we have the group of global nomads we met before, who have gone into ”global orbit” and have lost their ties to the ”local”, which is mainly associated with something negative, while globalism has become a sort of new nationality. In contrast to them, the top left corner of the figure shows the globalization enthusiasts, who have still retained positive links to their home country and ”local” matters. In the literature, this group are often referred to as ”grounded cosmopolitans” – they are globetrotters who have not lost touch with their roots and can still value and appreciate others who think in a more earthbound way and whose circles are smaller. These two groups are reflected in the bottom half of the figure, which contains people who lack global mindset – either because they can only see the positive in their own back yard, or because they are in a no man’s land where they do not feel part of either a national or a global community – perhaps because they are in a period of transition.

Do you have groups of employees who have actually become ”too” global in your organization? Have you yourself become ”too global”?

How do you ensure that the development of global mindset does not render employees unable to deal with more locally-minded colleagues and business partners? What are you doing to keep your own leadership practice grounded?

Are your career paths viable for hyper-global employees? What do the career paths mean for your own development opportunities?

Some companies put their trust in younger generations almost automatically having a more global outlook: they have travelled more, they are more global consumers of culture, speak better English and have Facebook friends in many countries. A more pessimistic gloss on younger people’s global competences, also represented among the members of the Global Leadership Academy, is however that young people simply can’t be bothered with postings abroad and the life of a global nomad. They like to Skype and enjoy travelling but do not want to settle abroad. One suggestion is to look at the job design and workflows, so people do not have to travel so much. Another is to go for the ”grey gold” instead, and choose more mature leaders to be posted and recruited into global jobs. They have the time and the energy, no small children, and the self-knowledge, broad-mindedness and tolerance gained from a long life (some research suggests that older people do better than younger ones in the international environment). So one answer might be to ”leave the young at home and send silverbacks to start up a new subsidiary in Mexico instead of retiring to play golf in Spain”.

Another solution, or course, is to go for ”self-initiated expats”, the rapidly-growing element of the global workforce who travel around themselves looking for work. This saves companies a lot of bother, as employees themselves bear the costs and the risk of international working and do not turn their noses up at ”local salaries” at a time when more and more companies are moving away from ”special compensation packages” for global employees.

And it is also a myth that there will be less need for postings abroad in the future – the consultancy firm Mercer runs regular surveys of this phenomenon and the findings indicate that expat postings as a global working practice happily co-exist with an increase in the number of people working globally in other ways, including European commuters, business travellers or virtual matrix employees.

How would you describe your view of millennials/”generation Z” in relation to global competence and global working?

How do you use job design and organization structures to support the development of global competence? Does your team/department allow you to arrange work activities differently?

Do you use the whole range of types of employment and recruitment channels to secure global competence? Are there types of talent that you do not pay attention to today?

An often unspoken idea about global competence is that, once you have acquired it, it lasts for life. At the extreme, you could say that the members of the Academy have had a tendency to talk about global mindset in a way that suggests that, once you have developed a global mindset, you will think globally for the rest of your life. If this were the case, global mindset competence would be quite unique, as most other competences have to be maintained if they are not to fall away, and are also tied to the context and situation in which they are used, so they have to be adapted to changing conditions along the way.

Research in this area is sparse, but not surprisingly there are signs that global mindset, like any other skill, can diminish and break down over time. Research has shown through global mindset profiling with individual global mindset tests that people who have had a high global mindset score at an earlier period of their careers characterized by a very global role, may actually score relatively low after a later spell in a more locally oriented job (Pucik 2006). The point is then that global mindset has to be maintained.

One of the authors of this book lived and worked abroad for many years and speaks several languages, so must presumably be very globally competent. Maybe, or maybe not, because that was all many years ago, so how much of it is left? What difference does it make that this person has been researching this area for many years in the meantime? And had a lot of foreign friends? The research does not give us a clear answer on the ”half-life” of global mindset, but it is interesting to consider what activities and other life experiences break down and develop global mindset – and whether the company or the individual leader have weighed the implications for their skillset.

How can you determine whether global competence is out-of-date – in yourself and other people? Have you taken a critical look at your CV to take stock of the state your global competences are in?

How can global competence be maintained? What are you as a leader doing to maintain and upgrade your global competence?

And are you ready to accept that a more locally oriented job might actually call for a certain breakdown of global competence if you are to remain competent in a new situation?

One of the studies carried out as part of the work of the Global Leadership Academy (Nielsen and Nielsen, 2016) clearly shows that many global leaders feel they have been left to themselves to pick up a global leadership role by ”learning on the job”. While there is certainly nothing wrong with either learning from colleagues or building up experience through practice (quite the opposite, in fact), these leaders also want help to develop globally. The same study also showed that many of the leadership development programmes that address global needs are global mainly in the sense that a) the programme is common to all the countries in which the company is represented; b) the programme is run in English; and c) the programme has a title containing the word ”global”. With regard to the actual content of so-called ”global” leadership development programmes, there was typically less that actually addressed involvement with global leadership. The network-building and accumulation of social capital which take place whatever the course content when leaders are brought together from different areas of the company should not be underrated, but the suggestion is that this is not enough.

Are the content, language and attendance in your leadership development programmes all global? Why/why not? Have you as a leader actively contributed ideas and problems which you particularly wanted included in global development efforts?

Which particular global competences are developed in your global leadership development programmes, and how? How does your own participation in global leadership development programmes help with your personal global development – and what can/should you yourself do to accelerate this learning process?

Does the HR department itself have the global competence it is trying to impart to others in the company? How can you as a leader help to push the work of HR in a more global direction?

How does the training you have received reflect/match the reality and the challenges you face as a global leader?

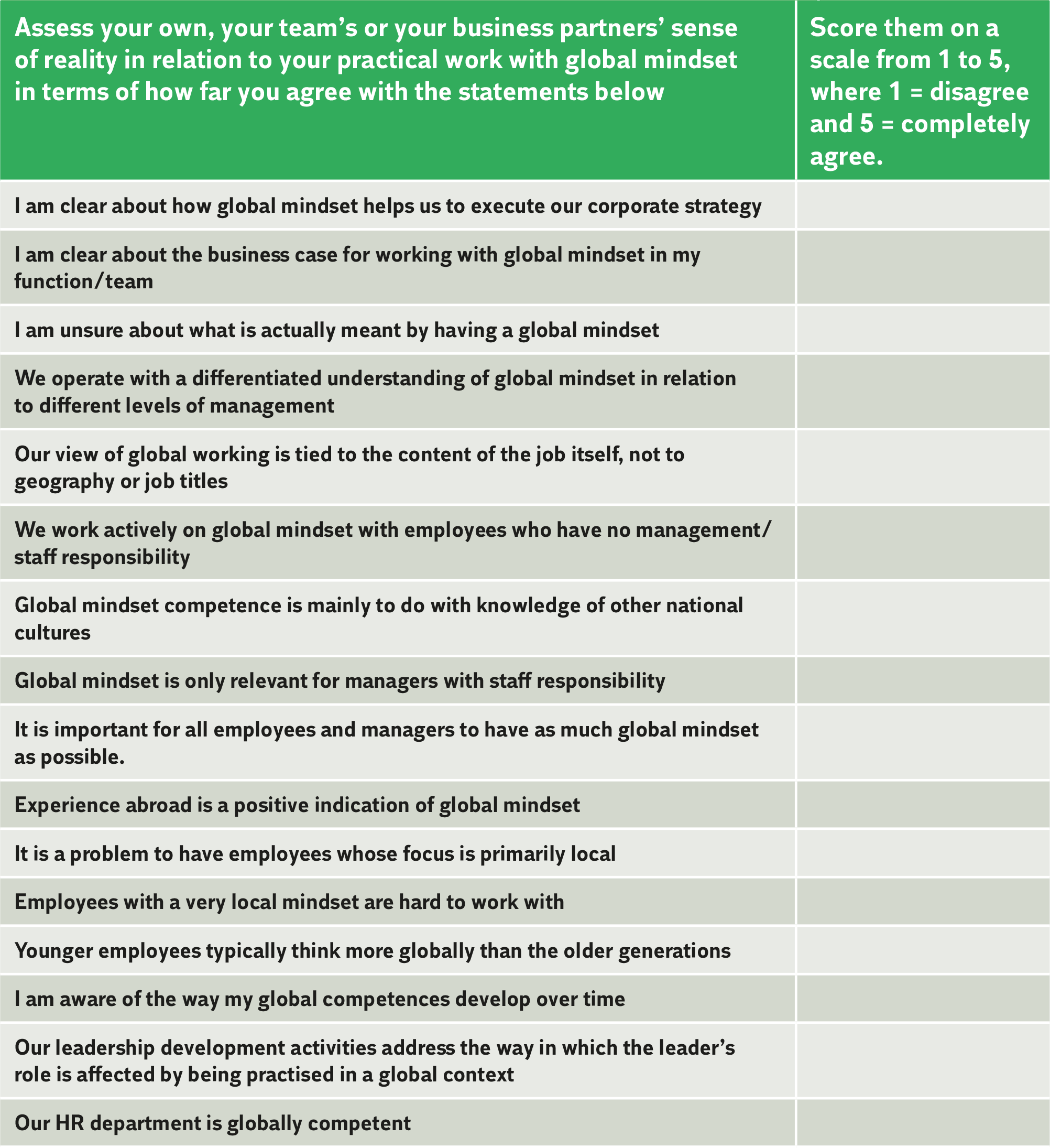

The self-test below summarizes the main points from the nine myths and gives you the chance to make an overall assessment of your own and your colleagues’ perception of working with global mindset in practice. As always, this sort of test works best if you are honest – and if you use it as a basis for discussion, ideally with others who may see things quite differently from you.

Figure 12.3: Global mindset reality check

Gertsen, M. C., Søderberg, A.-M. & Zølner, M. (2012). ”Introduction and overview”, pp. 1 – 14 in: M.C. Gertsen, M. C., Søderberg, A.-M. & Zølner, M. (eds., 2012). Global Collaboration: Intercultural Experiences and Learning. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Friedman, T. L. (2007). The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century. New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Storgaard, M. & Skovgaard, I. S.: (2012). Designing Organizations with a Global Mindset. Copenhagen: Global Leadership Academy/Dansk Industri og Copenhagen Business School.

Gupta, A. & Govindarajan, V. (2001). The Quest for Global Dominance. Transforming Global Presence into Global Competitive Advantage. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nielsen, R.K. (2017). Global Mindset in Context: Middle Manager Microfoundations of Strategic Global Mindset. Academy of Management Proceedings, Vol. 2017, The Academy of Management, 2017.

Nielsen, R.K. (2014). Global Mindset as Managerial Meta-competence and Organizational Capability: Boundary-crossing Leadership Cooperation in the MNC. The Case of ”Group Mindset” in Solar A/S. Doctoral School of Organization and Management Studies, PhD Series; 24, 2014.

Ghemawat, P. (2001). Distance still matters: The hard reality of global expansion. Harvard Business Review, 79 (8), pp. 137 – 147.

Ghemawat, P. (2007). Redefining global strategy: Crossing borders in a world where differences still matter. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.