Tool 8

Why: Global enterprises are often described as being particularly prone to conflict due to the challenges they face, e.g. increasingly complex demands for coordination across the organization, strong and varying expectations from stakeholders and constant organizational change, combined with linguistic and cultural differences and geographical distance. Many global leaders find that global collaboration raises particular demands for trust and that conflicts need to be prevented and addressed under different conditions than is the case in a local environment.

What: This tool zooms in on trust and conflict in global working, and looks at how building trust and handling conflict are complicated by language, cultural differences and geographical distance. In this tool, points to consider and questions for reflection on building trust and managing conflict will guide you towards a picture of where you as a leader can usefully step up and be more aware of conflicts which might otherwise fly beneath your radar.

How and who: The tool can be used by global leaders who want to strengthen their conflict management skills in global collaboration situations, and to prevent conflicts by proactive efforts to build trust.

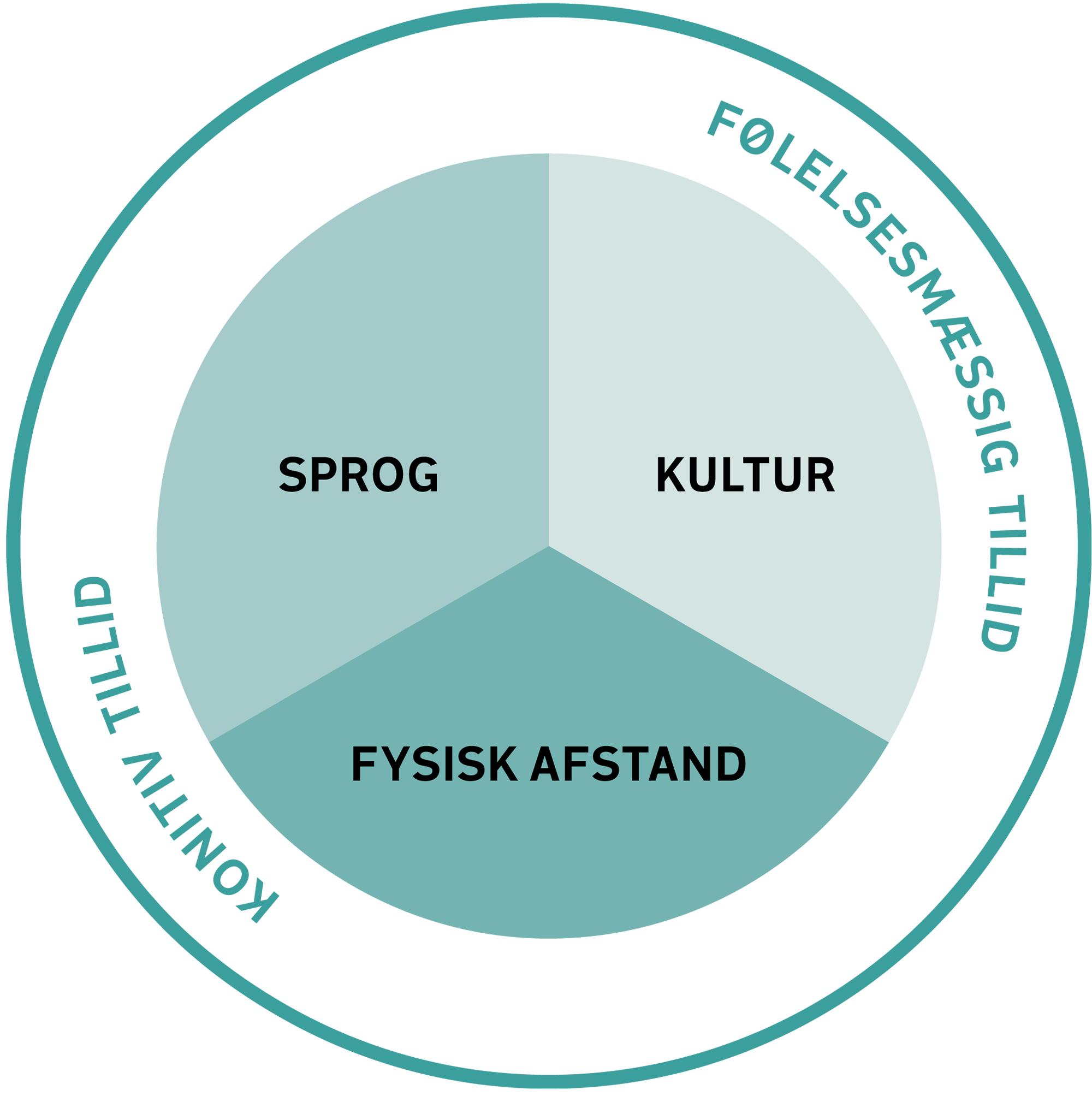

Trust is an essential factor in all types of collaboration, and conflict management is an inevitable part of the leader’s role. In global collaboration situations, however, there are some specific factors present which mean that trust has to be built up and conflict managed under different conditions and on different terms from those you are used to. This tool zooms in on three of these factors which make it harder to build trust and handle conflict, as shown in the figure below:

Figure 8.1: Building trust and managing conflicts in global collaboration

This section provides some food for thought on how linguistic and cultural differences and geographical distance affect trust and conflict in global collaboration, and how a leader can address the challenges and capitalize on the opportunities.

Not surprisingly, a high level of trust among employees who are geographically dispersed has a positive effect on satisfaction and well-being in the team members, and a high level of trust also affects communication and performance in the work of individual global employees. Trust among global employees also affects their acceptance of different values and attitudes held by their colleagues. People working in global teams with a high level of trust are often better at acquiring the knowledge that they need from each other from day to day.

We can distinguish between two different sorts of trust:

BIf we study trust in a global context, it is particularly interesting to look at three forms of difference that can each have a crucial influence on trust or the lack of it: language differences, cultural differences and geographical distance, as illustrated in the figure below:

Figure 8.2: Trust in global collaboration

Language differences can have a very adverse effect on cognitive trust because we often tend to see a lack of linguistic skills as a lack of cognitive ability in general. So the harder you find it to express yourself in English, for example, the less competent you may be perceived to be. The same is true of your staff and colleagues.

This negative effect can be addressed in several ways. First and foremost, it is important for both the global leader and the members of the team to be open about each other’s differences. Consistent use of a common company language can also have a positive effect on trust within the team. Team members who do not have a strong command of the company language will often tend to worry about how others see them, precisely because they are aware that colleagues and managers may get the impression that they are not as competent as those who find it easier to speak the common language (which will often be English).

Points to consider:

There will often be lots of cultural differences in a global organization, and these can have a negative effect on trust within the team unless an effort is made to deal with the differences represented by employees from differing cultural backgrounds. This is because the members of the team may find it hard to interpret the cultural markers that they each bring into the collaborative mix – particularly if they have no experience of global collaboration. People from different cultures will typically tackle and judge these aspects in different ways. This means that they need time to find common ground and make room for the diverse views and approaches. Employees who are not aware of their own culturally-based preconceived opinions, prejudices and expectations may have a tendency to regard colleagues from other cultures as less professional.

Cultural differences can have quite a big impact on affective trust. That is why relationships between people from different cultures tend to be less personal. Particularly if they also play out in a context where there are geographical distances between colleagues, so they rarely have the chance to meet physically. Danish global leaders can find it particularly hard to forge personal relationships as, unlike many other nationalities of global leader, they are liable to take affective trust for granted and do not display their feelings as much as other global leaders.

Points to consider:

Geographical distance can make it difficult for global team members to identify with each other and reach an understanding of what they can each contribute to the collective. And it is often difficult for the global leader to follow up when their staff are working in different locations. One way of building trust and improving efficiency is for the global leader to arrange meetings where they are there in person. Particularly at the start of the collaboration, it is a good and important investment for the leader to make. It is also advisable for the global leader to be clear about the expectations of the individual employees and their role in the team. Well-defined goals should be set for each team member, to prevent mistrust arising from a lack of clarity as to the individual’s contribution to the collective results.

Points to consider:

Building trust is a bulwark against disagreements escalating into conflicts. Even though the global leader may be working hard to build trust, conflict handling is an unavoidable part of the role, and it is advisable in this situation to pay particular attention to the extra challenges that global leadership brings to conflict management.

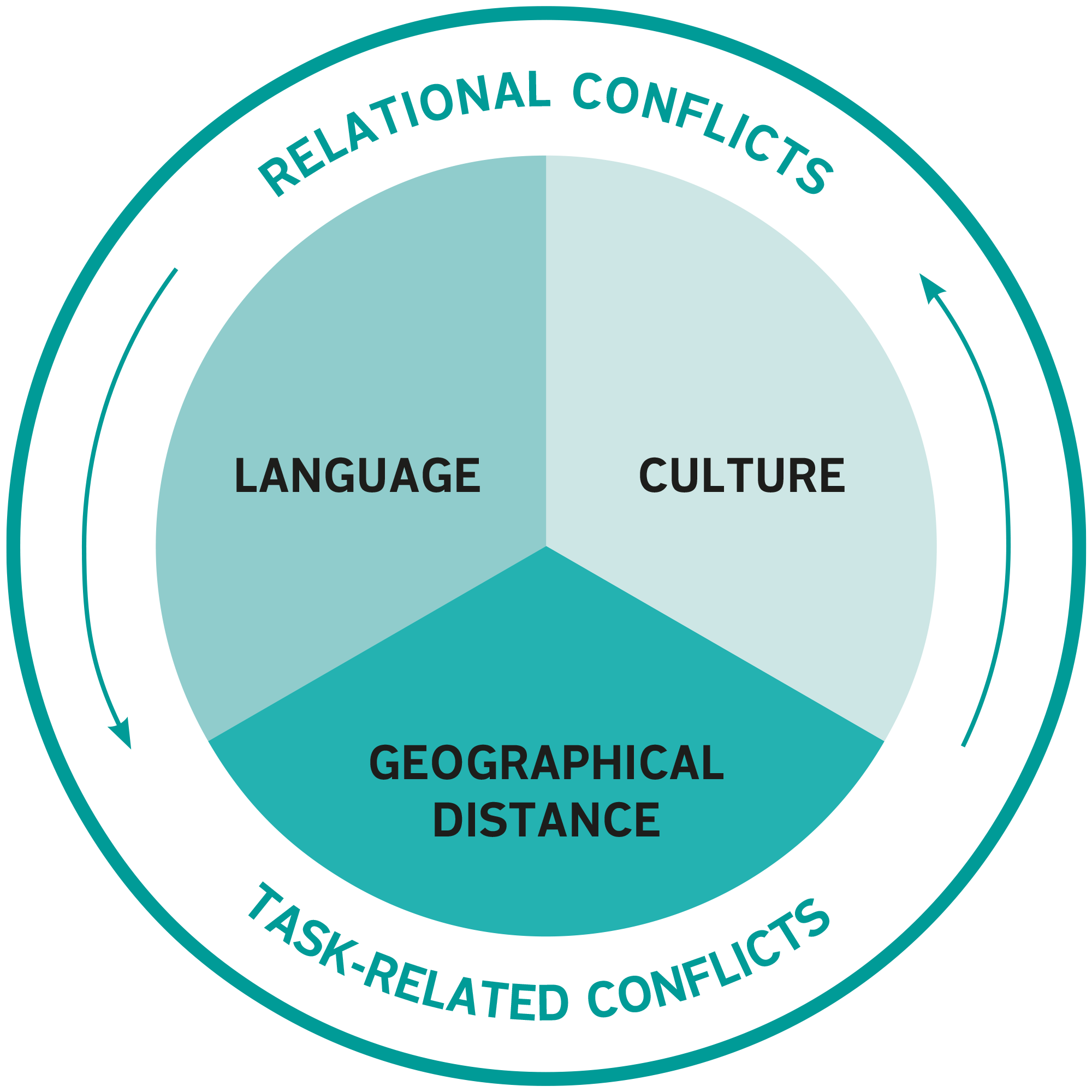

In this part of the tool, we will be working with two types of conflict in global collaboration:

As with the section above on trust in global collaboration, this section looks at the three dimensions: language, culture and geographical distance, and how these three aspects affect relational and task-related conflicts in global collaboration, as illustrated by the figure below:

Figure 8.3: Conflicts in global collaboration

In contrast to relational conflicts, task-related conflicts are often more neutral in their effects on the final work product. Task-related conflicts may be good for the development of the team – not least technically if they are handled constructively, but it is important to bear in mind that a task-related conflict can easily develop into a relational conflict with the resulting negative impact on the performance of the parties involved and of the team.

Conflicts within global teams and between global business units often arise when global employees have opposing personal and professional goals. Just as many conflicts arise when there is a lack of cognitive and affective trust. Often conflicts come out of organizational pressure and the complexity that comes with working in a global context.

Many people find relational conflicts more damaging than task-related conflicts. It is also clear that relational conflicts have a harmful effect on key aspects of the work within the team. Relational conflicts typically affect team members’ performance, commitment, communication and satisfaction. They also influence how open employees are towards other cultures.

Language: Language differences can act as a driver for conflict. This means that big linguistic differences within the team can be a contributory factor where the incidence of conflicts is greater in some teams than others. However, global leaders can actively counteract this by arranging language training and by looking for staff with good language skills – both in recruitment situations and when assembling the team.

There is also a tendency for the number of conflicts in an organization to increase with the number of languages spoken in the company.

As with trust, global leaders could therefore consider using a common company language at all times and offering language training to their staff.

Culture: Cultural differences may also act as a driver for relational conflicts, particularly if there is a lack of respect and understanding of the cultural differences within the team. Culture also affects the way in which employees express their disagreements, and there will also be differences in how sensitive the individuals are to cultural matters. Both as individuals and as a consequence of their separate national cultures.

To prevent relational conflicts arising out of cultural differences, the global leader may need to display a high level of cultural awareness in handling conflicts and always strive to build personal relationships with his/her staff, so individuals feel both noticed and understood by their manager.

The leader can also use a supportive leadership style in situations where conflict-averse employees try to express personal concerns, so they feel it is both safe and acceptable to raise matters they are not generally comfortable addressing.

Geographical distance: Physical separation can cause relational conflicts to flare up. Employees who are geographically dispersed may then tend to use a harsh tone and often escalate conflicts to the management level instead of taking action themselves. Here it is important for the employees to meet face to face, both to defuse existing conflicts and to prevent new ones arising in the future. The insight and mutual understanding that can help to reduce the level of conflict are best achieved when people meet in physical space and not always just virtually.

The leader can also consider implementing guidelines and policies for good conduct in virtual collaboration, to provide a basis for constructive teamwork across countries and cultures.

Conflict management – managing relational conflicts

To address relational conflicts, you need to take action at the individual, the team and the organizational level. At the individual level, processes such as training, coaching and mentoring can help to keep relational conflicts down. At the team level, team-building activities can help to improve social relationships and clarify the roles of the team members. Team-building is particularly effective in teams faced with emotional issues and relational conflicts. At the organizational level, strategies and policies can be implemented to prevent conflicts.

Task-related conflicts can have both constructive and destructive effects. These task-related conflicts may stimulate employees’ commitment to the group’s tasks in organizational settings, as groups whose members produce different competing proposals to be talked through in depth are more likely to reach higher-quality decisions. Discussing tasks within the group can lead both to better solutions and to more positive feelings and attitudes among the employees. At the same time, task-related conflicts may not necessarily enhance the positive group processes as they can be time-consuming and also result in issues with relationships within the team.

Task-related conflicts can develop over time into relational conflicts if they are not handled constructively and in time. To prevent this, it is important to have clear agreements on how the team should handle the task-related conflicts before they develop into relational conflicts. The leader could also bear in mind that a constructive level of task-related conflicts might actually be an advantage to the team if they are handled constructively.

Language differences: The importance of language in task-related conflicts is much the same as for relational conflicts. This means that, the more you do to improve the language skills of the people in the team, the more smoothly things will run in their work on day-to-day tasks and long-running projects. Agreements to the effect that everyone should communicate in the same language will also help to reduce the incidence of task-related conflicts, as the employees will be able to get involved – if not all on an equal footing, then at least on equal terms.

Cultural differences: Global leaders need to keep in mind that some people are more sensitive to conflicts than others, and that employees with this sort of cultural baggage will often seek to avoid controversial subjects. By respecting these cultural differences – and creating a safe framework for discussion and debate within the team, the leader can try to produce an environment where the employees feel it is permissible to raise subjects that not everyone may agree on, and which not everyone finds it easy to bring up at meetings and in conversation.

Geographical distance: Where there are geographical differences, many people will find it much easier to start a conflict with a person they have met in a virtual forum – and so have contact with only at a distance – than with a colleague they have met face to face. So it makes sense to gather the relevant team members together when new projects are launched. The same applies to the tone in which people communicate when the team is to work together, whereby there is a clear tendency for employees to use less harsh language when they have been together in the same place and had the chance to build a stronger relationship.

Conflict management – managing task-related conflicts

Task-related conflicts are much less damaging to collaboration than relational conflicts. That is why it is important for global managers not to shy away from task-related conflicts, but to create an environment which supports the ability of the staff to express their task-related disagreements. It is good for the global leader to display openness towards different points of view though his/her behaviour, which may then inform the behaviour of the team members in their day-to-day work – a good objective discussion of professional disagreements can be productive for the team.

The challenge for the global leader is to limit disagreements to task-related conflicts so they do not develop into relational conflicts. One way of tackling this might be to agree on a number of ”ground rules” for the work of the team, which could include agreements on how to talk to each other and how ”direct” a tone is acceptable across all cultures and employees.

It is important for issues between team members to be addressed right at the start of the relationship in order to prevent disagreements developing into relational conflicts, and the global leader needs to show the will and the ability to engage in personal relationships and to display openness, respect and understanding of the differences between employees, as this will often minimize the risk of conflicts.

”There are many subtle conflicts. It is not something that people are really upset about here [at the parent company, ed]. But over time, the small things turn into a dismissal here and a project that is abandoned there. But it is these little everyday things. Perhaps they build up more. It’s harder to get them aired out in relation to those who work from a distance.”

(Danish global leader quoted in Lauring & Klitmøller, 2014, p. 40)

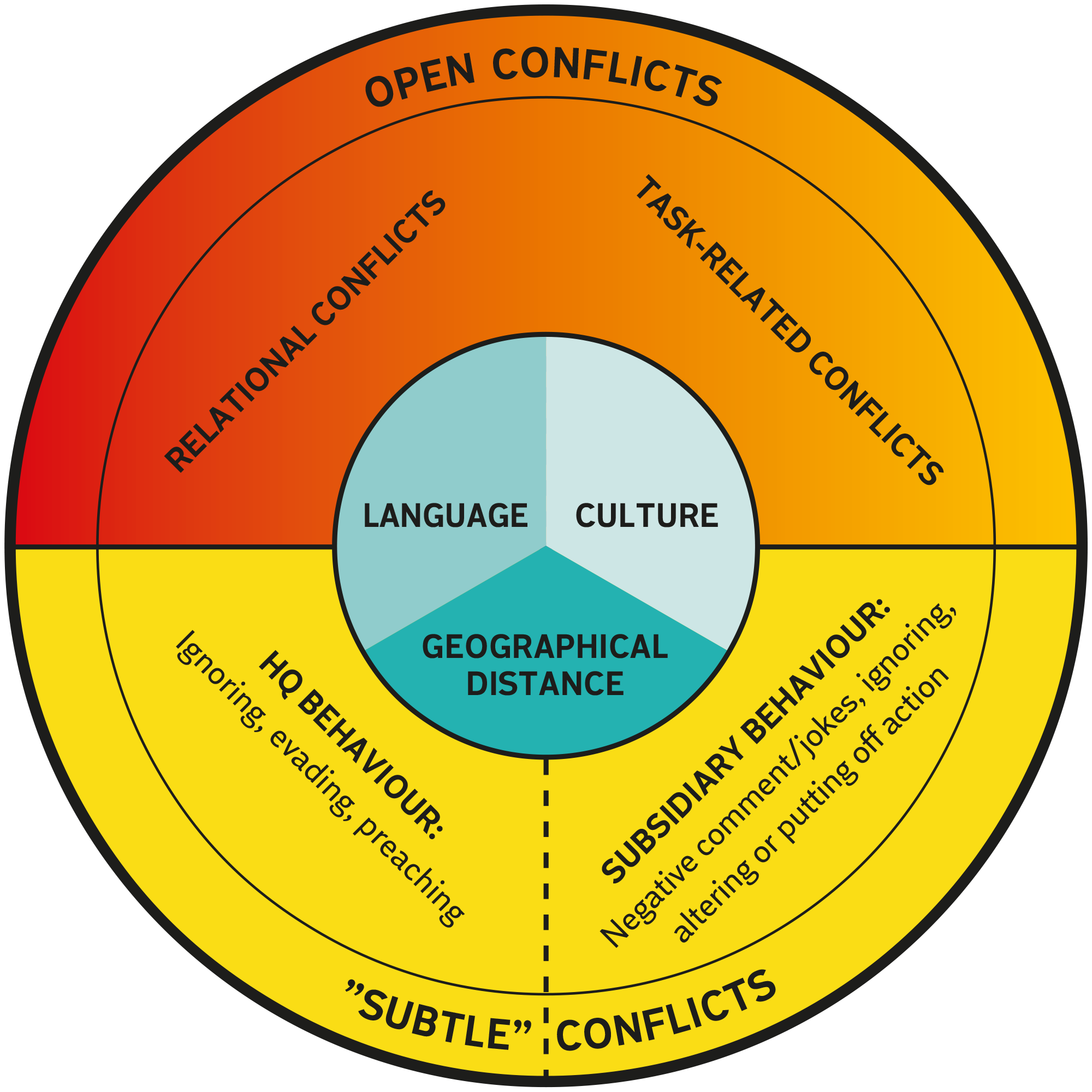

The absence of open conflicts is not necessarily a healthy sign. If you are not experiencing any conflicts in your team, it may be because the team is not interacting enough to have any conflicts in the first place. If you are not experiencing any conflict as a leader, it may also be a sign that there are conflicts going on under the surface – what we call ”subtle” conflicts, characterized by being less intense than an open conflict, but still essential to spot and to address.

Low-intensity conflicts are relatively common in global companies and can have a serious adverse effect on collaboration in the global organization. These conflicts often arise out of opposing positions of power within the company, typically between head office and subsidiaries. It then often happens that the superior party, who will often be located in the parent company, looks the other way in conflict situations. This is illustrated in the figure below, which distinguishes between open conflicts and subtle conflicts and the ways in which subtle conflicts come out into the open and arise in headquarters and subsidiaries respectively.

Figure 8.4: Open and subtle conflicts in global collaboration, focusing on the relationship between HQ and subsidiaries

It is extremely problematical to turn a blind eye to this type of conflict, as low-intensity conflicts can help to delay projects and make it difficult to produce the necessary results in the different units within the company. There are three types of HQ behaviour that can typically lead to low-intensity conflicts.

The first HQ behaviour is to ignore, which happens when managers and staff in subsidiaries feel that the global leaders and specialists at head office are not listening to them or taking their advice into account.

The second HQ behaviour is to avoid or circumvent, which is particularly prevalent in global organizations. Such conflicts arise when managers at head office take the view that input from the local managers and the subsidiaries is irrelevant to implementing global policies and processes. Conversely, employees in the subsidiaries often view these initiatives as obstacles, and conflicts arise out of this.

The last HQ behaviour is preaching, a sort of preachy tone taken by managers in the parent company. While this is often done with the best of intentions, it is perceived as arrogant and can cause employees in the subsidiaries to keep silent. It is important for the global leader to remember that the local employees are the local experts and are essential to the success of the whole global organization.

The reaction in the subsidiaries to these types of HQ behaviour may often be felt only in the form of passive-aggressive behaviour such as negative comment or cynical jokes about head office or by initiatives from HQ being ignored, put off or altered significantly along the way.

Conflict management – managing subtle conflicts

It is important for issues between team members to be addressed right at the start of the relationship in order to prevent disagreements developing into relational conflicts, and the global leader needs to show the will and the ability to engage in personal relationships and to display openness, respect and understanding of the differences between employees, as this will often minimize the risk of conflicts. To reduce the number of low-intensity conflicts in the company, the global leader should:

What are you best at – building trust or managing conflict? And where are your weaknesses? Give examples

Think of a difficult situation that was resolved in a good way: What did you do in that situation that worked well? What did you not do?

What could you do more or less of in the future in order to build trust?

What could you do more or less of in the future in order to prevent and handle conflicts?

Who could you usefully involve in your efforts to build trust and handle conflicts?

What performance or process targets can you define for your work in building trust and managing conflicts in global collaboration?

Lauring, J. & Klitmøller, A. (2013). Global Leadership Competencies for the Future. Trust and Tension in Global Work. Global Leadership Academy – Danish Confederation of Industry and Copenhagen Business School.

Sønnichsen, H. & Buron, C. (2015). Communicate your way to success. GLA Insights, June 30, 2015.

Straub-Bauer, A. (2015). Language skills are more important than you think. GLA Insights, March 12, 2015.

Straub-Bauer, A. (2015). When headquarter staff contributes to conflict. GLA Insights, February 23, 2015.